Cubicle

The most static object is still in motion at a molecular level and the world is always changing. Even if the object was this perfect thing that stayed the same, we as a society change how we view it. My installations are about destruction and creation, and they generally have no static point. It is the process of changing them that is the point.

- Jonathan Schipper

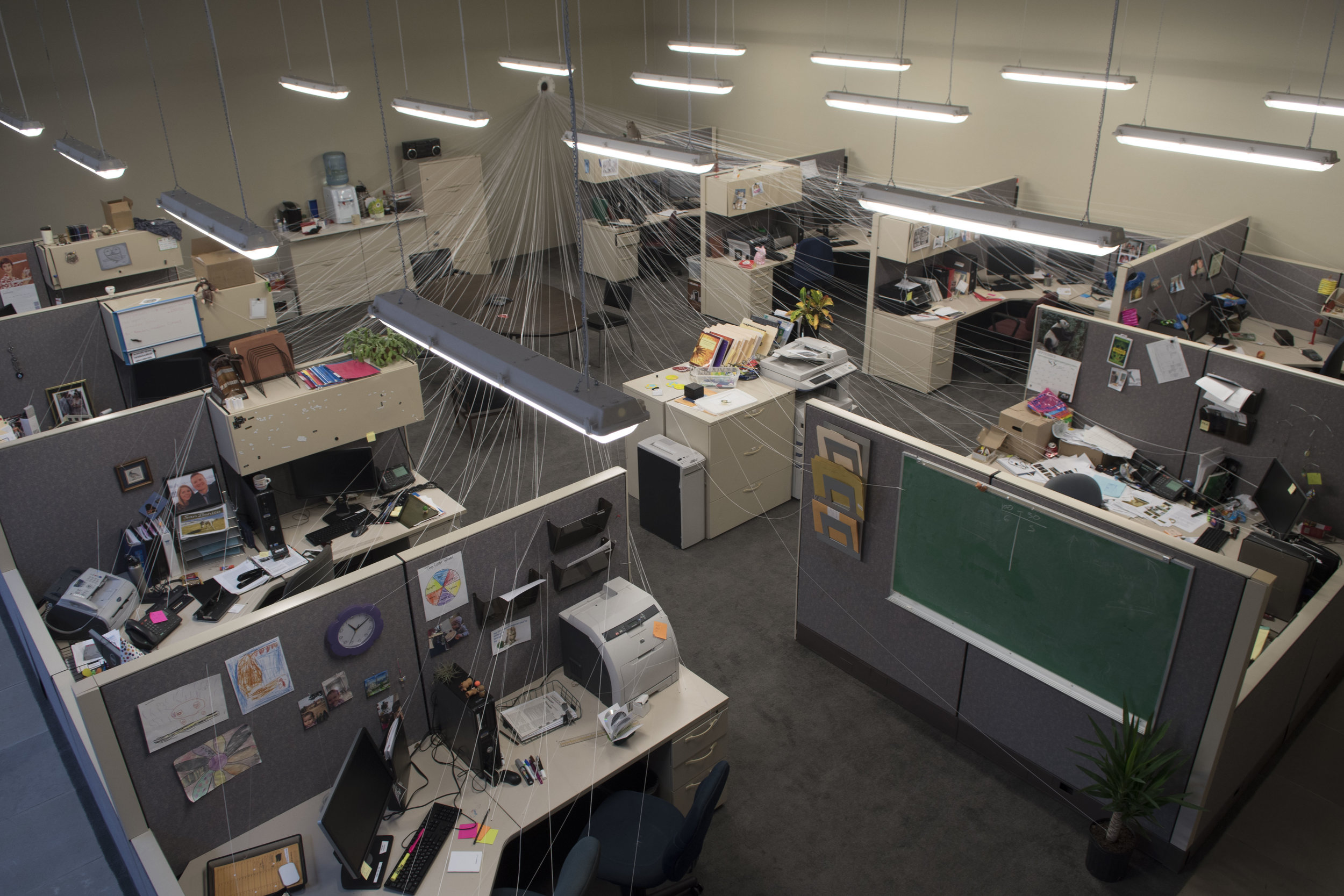

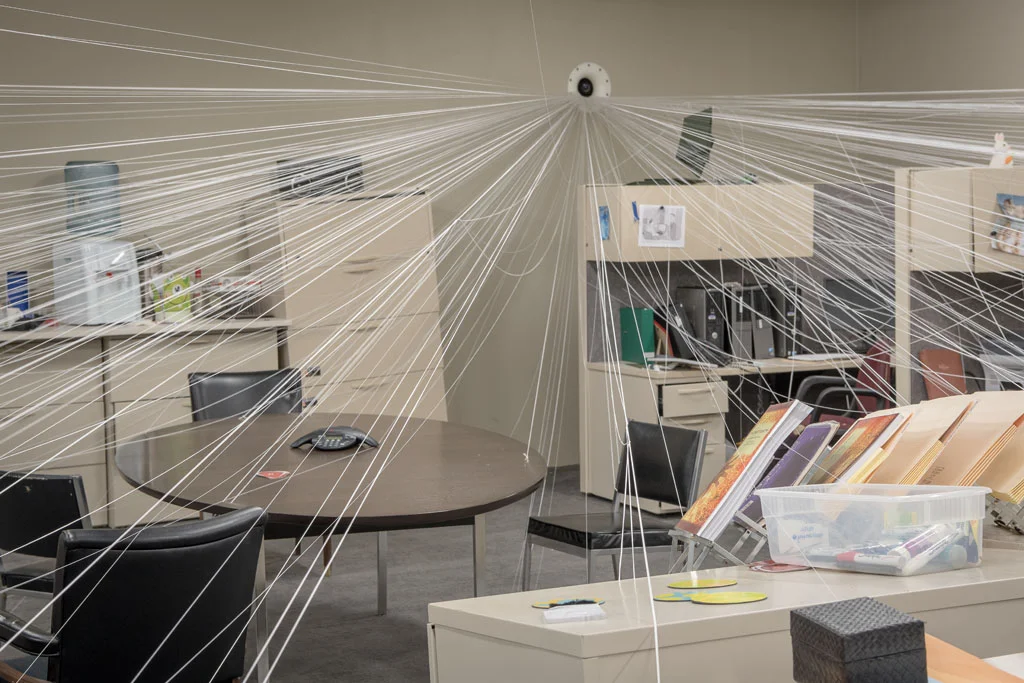

Walking by Rice Gallery and quickly glancing through its front glass wall, it might be easy to mistake it for a functioning office space. A grid of fluorescent lights hangs from the ceiling and cubicles line the perimeter of the gallery, surrounding a conference table and copy machine. Each workstation is full of the all-too-familiar trappings: boxy Dell computers, stacks of manila file folders, and personal ephemera pinned to cubicle walls, such as family photos and motivational messages. Far from the pristine, paperless ideal of the digital age, Rolodexes, adding machines, zip drives, and other dated technology litter the desktops. A dense web of cables interrupts the placid scene and is the first clue that this is not a normal workplace. The lines connect nearly every item in the office to a mechanical winch hidden behind a wall in the gallery’s back corner. The machine continuously pulls the objects and furniture at an extremely slow speed toward a small hole in the wall and eventual collapse.

New York artist Jonathan Schipper is known for his time-based, kinetic installations that reveal the flow of time as imperceptible until, as in life, we see the physical evidence of its passing. To achieve this, Schipper customizes mechanical winches to run at unusually sluggish rates. These winches, commonly used in tow trucks, elevators, cranes, and boats, are for pulling in or letting out cable to move or suspend heavy weights. For example, to create the Slow Inevitable Death of American Muscle, 2008, Schipper modified such a device to crush two full-size Pontiac Firebirds into one another to simulate the force of a 30 mph head-on collision decelerated to unfold over several days. For his Rice Gallery installation, Cubicle, the mechanical winch is powerful enough to pull 45 tons and is set to a timer to run continuously during gallery hours. Day-to-day changes are subtle, moving the lines approximately one millimeter per hour. Visitors can view in the Rice Gallery video space, adjacent to the gallery, a time-lapse video that will be updated to document the installation’s slow destruction over the two-month exhibition.

Cubicle is Schipper’s largest work in his ongoing Slow Room series. For his installation, Slow Room, 2014 in State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Schipper drew upon the museum convention of the period room, where from behind a barrier visitors could see a cozy-looking, old-fashioned American living room that over time became a chaotic clump of debris. Attracted to cultural obsolescence, he chose a cubicle-filled office space for his Rice Gallery installation as a non-domestic period room that we cannot enter, but instead view at a slight remove as a symbol of a not-too-distant past.

The cubicle began in the 1960s with the promise of increased workplace comfort and privacy for employees and has now fallen out of fashion with the reemergence of the open-plan office. With its utopian veneer stripped away, the basic office cubicle may conjure despair and entrapment. In Cubicle, Schipper mixes this dread with what might be for many the pleasurable prospect of demolition. Each work area is carefully stylized to reveal a different personality of its inhabitant: papers pile high at the desk of a messy officemate, anime characters decorate a video game enthusiast’s desk, and a proud employee displays collectible owls, the mascot of Rice University. These are the professional and personal artifacts that seem to endlessly accumulate and mark the hours and hours spent in the office as employees unconsciously grow into their work environments, some days busily working or others waiting for the clock to strike 5:00 pm. The plodding and inevitable annihilation of the staged scene heightens our awareness of this passing time.

Josh Fischer